Faith and power: Review finds religion overrepresented in Colorado's legislature

Published by Colorado Politics on June 24, 2023.

* * *

Colorado lawmakers open every morning of the legislative session with a group prayer on the chamber floor, recognizing their religious beliefs and often asking for guidance from their respective God before beginning policy work.

But a growing number of legislators spend this designated prayer time waiting in the hall.

Of Colorado's 100 state lawmakers, 24 identify as nonreligious, including atheists, agnostics, humanists and more. That's according to a first-of-its-kind survey by Colorado Politics, featuring 73 direct responses from lawmakers, as well as public identifications from campaign websites, religious caucuses and legislative debates.

When looking at population and affiliation, the data shows legislators in Colorado's General Assembly are considerably more religious than the constituents they represent.

(Data from the Public Religion Research Institute's 2022 audit and Colorado Politics' 2023 survey conducted by Hannah Metzger. Graphics by Tom Hellauer/The Denver Gazette)

More than 1 in 3 Coloradans, 34%, are religiously unaffiliated, according to a 2022 audit by the Public Religion Research Institute. This roughly aligns with the most recent data from Gallup, which found that 38% of people in the Rockies region were not religious in 2017, and Pew Research Center, which found that 29% of Coloradans were not religious in 2014.

The disparity between Coloradans and their legislators is the most stark for the nonreligious, with a difference of minus 10 percentage points. Colorado's Christian, Jewish and Muslim populations are all proportionately represented or overrepresented among lawmakers.

Religion in the halls of power

Rep. Judy Amabile, an atheist, said when people learn of her beliefs, they often ask if she is at least spiritual. The Boulder Democrat said many seem disappointed when she tells them no. But Amabile believes religion isn’t necessary to be a good lawmaker, saying she doesn’t “need to believe in something mythical to keep me going on the path that I'm on in terms of trying to solve problems.”

Amabile said she has a friend across the aisle in the legislature who has encouraged her to convert to Christianity. During one floor debate on Amabile's bill to provide housing vouchers to homeless foster youth, the friend fought against the bill, arguing that once foster kids turn 18, they're responsible for themselves.

"When the hearing was over, I said to this person, ‘I think I have better Christian values than you do,’" Amabile said. "I was kind of only kidding, but we somehow equate religion with morality or good values and they're not related. You shouldn't have to be religious for people to think you are a moral person."

Aside from the morning prayer, religion is often present in the state legislature.

A Bible study for lawmakers is held in the Capitol every Tuesday, lawmakers frequently quote scripture during policy debates, and, last session, party leadership feverishly worked across the aisle to negotiate the end of stall tactics to give lawmakers the day off to attend Good Friday and Easter services.

House Minority Leader Mike Lynch, a Christian, said recognizing religion in the legislative process helps lawmakers to remember the foundations of religious freedom that founded the United States. And for religious lawmakers like him, it honors the influence that religious beliefs have on their policy work.

“I don't make any decisions, especially ones that involve morals, without checking my faith first,” Lynch, R-Wellington, said. “It's so integral to every decision that I make. I would never legislate anything that I felt went against my biblical knowledge or my biblical beliefs.”

Rep. Iman Jodeh, Colorado’s only Muslim lawmaker, said her faith similarly guides her legislative work. It colors both specific policy positions and her general values — particularly regarding advocating for marginalized groups.

"The values that my religion believes in very much coincide with what it is to be a progressive Democrat,” Jodeh, D-Aurora, said. “Sometimes, I am a state legislator who happens to be Muslim, and there are times where I am a Muslim who happens to be a state legislator. It's so interchangeable.”

Jodeh often speaks about her faith on the House floor, making announcements to celebrate holidays, such as Ramadan and World Hijab Day, and giving the morning prayer herself numerous times. But Jodeh said she’s intentional about not crossing any lines, never quoting religious texts in debates and using language that is inclusive to all religions in the morning prayer, such as saying, “In his many names we say amen.”

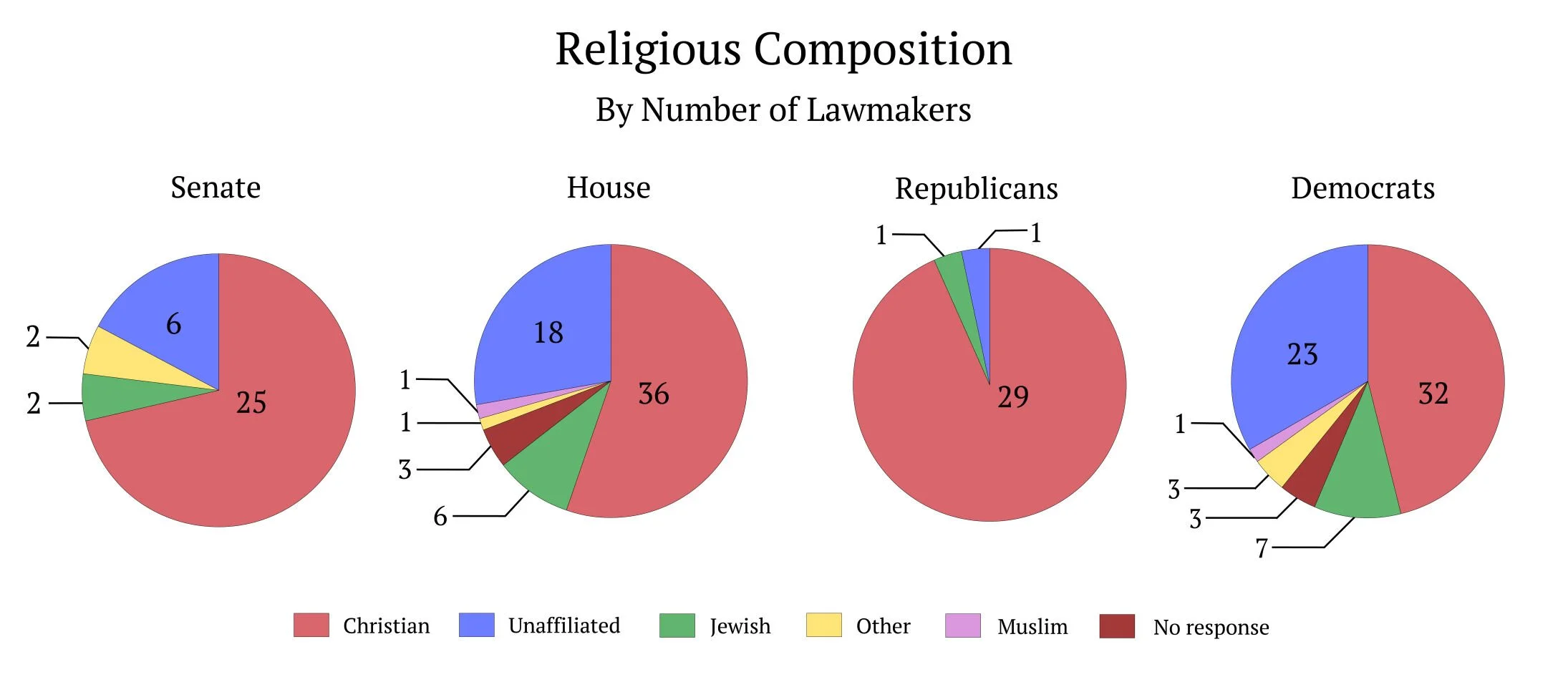

Democrats make up almost all of Colorado’s lawmakers who are nonreligious, and who are religious but not Christian. Of the 31 Republicans in the legislature, 29 are Christian, one is Jewish and one is nonreligious.

(Data from Colorado Politics' 2023 survey conducted by Hannah Metzger. Graphics by Tom Hellauer/The Denver Gazette)

Rep. Ryan Armagost of Berthoud is the sole nonreligious Republican. Armagost, who is agnostic, said he believes in a higher power but doesn’t put a name or religion to it. While Armagost said nonreligious is an accurate description for him, he said he appreciates many different religions.

Armagost said the morning prayer and other religious activities in the legislature don’t bother him, pointing to “freedom of religion.”

"Faith in one form or another is good," Armagost said. "I think it's something that we all need at the start of each day. If people are uncomfortable with it, I think those are more the people that are just anti-religion."

Senate Minority Leader Paul Lundeen, a Christian, said he doesn't think religion is incorporated in the legislature "in a meaningful way." While Jodeh steers clear of citing the holy books, Lundeen said he uses religion as a source of wisdom to inform his policy work, like one might do with philosophy.

"I have, in the course of debate in the well, quoted the Torah, the Quran, Kahlil Gibran and the Bible — all what I would describe as wisdom literature," Lundeen, R-Monument, said. "The use of wisdom as people derive it is fundamental to successful policy on behalf of the people."

Lundeen said the morning prayer is similar, representing numerous kinds of faiths to share differing perspectives on wisdom.

As an atheist, Amabile said she finds the morning prayer uncomfortable, which is why she’ll sometimes wait in the hallway during it. But she’s not interested in trying to get rid of it, saying she doesn’t “want to get involved in a culture war.”

When told the survey showed roughly a quarter of her colleagues are nonreligious, Ambile said she isn't surprised. She said the group waiting just outside during the chamber's morning invocation has grown substantially since she took office.

Rep. Lorena Garcia, an Adams County Democrat who is nonreligious, said she has questioned the need for the prayer with her colleagues and House leadership. She said she's always told it is a matter of tradition.

“It doesn't make sense to me. I think it's a waste of time,” Garcia said. "An entire third of the population doesn't pray. If you're going to pray, pray on your own time.”

Jodeh said the morning prayers contribute to the richness of the chamber by featuring leaders of all different faiths — and occasionally even of no faith. Lynch pointed out atheists have read aloud poems in place of the prayer before.

But Jodeh said not all of the speakers are as inclusive and sensitive as others.

“There were definitely times where it felt like I was getting a sermon rather than a policy perspective,” Jodeh said of the most recent legislative session. “I think that sentiment was shared among quite a few of my colleagues, unfortunately. If tomorrow we decided no opening prayer, I would honor that. I would understand."

Identifying boundaries for expressing religious beliefs has been a longstanding battle under the gold dome.

In 2017, during a memorial speech on the House floor for former Colorado U.S. Sen. Bill Armstrong, then-Rep. Lori Saine led the chamber in chants of "Jesus! Jesus! Jesus! Praise Jesus." Saine declared Jesus is "the only name that saves" and offered pastors to "pray over" any lawmakers who felt a "tugging at their heart." Afterwards, lawmakers were given pins with the chant "Jesus, Jesus, Jesus" on them.

Rep. Dafna Michaelson Jenet, who is Jewish, said this is one of many examples when lawmakers have crossed the line when it comes to religion. Michaelson Jenet was a brand new lawmaker at the time, and she made an announcement to the chamber about how the chants made her and other non-Christian lawmakers feel uncomfortable.

"We dance perilously close to lack of separation (of church and state) in some of the ways that we work," Michaelson Jenet, D-Commerce City, said. "This should be a place where many religions or no religions feel free to state their values and do their work."

Lynch said religious beliefs are necessary for someone to be a good lawmaker, adding it is "shocking" that 24 Colorado legislators identify as nonreligious.

"Having the humility of understanding you are not or cannot be a god gives you a perspective that I believe is necessary to do good legislation," Lynch said. "The humility of that acknowledgment of a higher being allows you to be a better legislator. ... I could not fathom doing this job without the level of faith that I have."

Garcia said religious lawmakers have at times challenged the motivations or policies of nonreligious colleagues based on their own faith.

"We are being attacked by someone who is deeply, devoutly committed to their faith, using their faith book," Garcia said. "I mean, God, how many times was the Bible quoted during debate? That is not going to sway anybody. That's not the reason why we're here making these policies."

Faith on the campaign trail

Identifying as nonreligious was once seen as a death sentence for politicians.

In 1958, only 18% of Americans said they would vote for a qualified presidential candidate who was an atheist, according to a Gallup poll. That number raised to 60% in 2019, but it’s still the lowest approval for any religious identification: 95% of Americans would vote for a Catholic president; 93% would vote for a Jew; 80% would vote for an evangelical Christian; 66% would vote for a Muslim.

Nationally, only two members of Congress are openly nonreligious, less than 0.4% — a far cry from the nearly 27% of Americans who were religiously unaffiliated in the 2022 audit.

"That's part of the formula for a politician: straight, Christian, white, man," Garcia said.

Matthew Server, associate director of the Colorado Catholic Conference, said religious people may be more likely to want to get involved in politics to shape the community because of their faith.

“From the Catholic perspective, there is a moral obligation to participate in public life and participate in the shaping of public discourse," Server said.

He added: "The Catholic Church has long stated that Catholic values belong in the public sphere, and that separation of church and state does not necessarily require division between belief and public action. ... Forming your conscience based on Catholic social teaching and the scriptures is incredibly important."

Dheepa Sundaram, a religious studies professor at the University of Denver, said the overrepresentation of religion in politics comes from the sheer prevalence of religion in the United States, particularly Christianity. She said people who are not religious but raised in close proximity to Christianity, or even people of different religions, are often socialized to believe Christian values align with the public interest.

When voters favor religious candidates for these reasons, it can create a sort of cycle of stigma, Sundaram said. Without identifiable representation of certain religions or nonreligious communities, voters perceive the differences between them as more substantial than they are.

"When we have a legislature that predominantly represents one particular religious community, the implication is that other religious communities wouldn't as much reflect our values," Sundaram said. "This can translate into these kinds of biases."

Even when there is nonreligious representation in politics, voters often aren't aware of it, making it easier for biases against nonreligious politicians to persist, said Ron Millar, political coordinator for the Center for Freethought Equality, a nonprofit that advocates for the atheist community.

While 24 Colorado lawmakers are nonreligious, they shared this information with Colorado Politics with the promise of anonymity, except for those who agreed to be interviewed for the article. While a number of the nonreligious lawmakers are open about their beliefs, this information is rarely available to the public.

Only six Colorado legislators are registered on the Center for Freethought Equality's list of elected officials who are nonreligious — all of whom are House Democrats. Garcia and Armagost bring the public tally to eight, after going on record as nonreligious in this article.

"People have to recognize that the nonreligious are their neighbors, friends, relatives and just regular Americans," Millar said. "And one of the best ways to do that is to have elected officials who publicly identify with our community."

Colorado is still ahead of most of the nation in terms of nonreligious political representation.

Only New Hampshire and Vermont have more openly nonreligious state lawmakers, eight each. But they have much larger legislatures, meaning Colorado has the highest percentage overall. This tracks with Colorado's status as the state with the fifth-highest religiously unaffiliated population in the country, according to the Public Religion Research Institute.

As a Republican, Armagost said he was frequently questioned about his agnostic beliefs when campaigning for office, but when he explained that he believes in a God, most people were understanding.

“I think being an atheist and a conservative is a lot more of a stretch. But I do come across that a lot,” Armagost said.

He continued: “If there's somebody in my political party that believes that I don't fit into their ideology because of my religion, then they themselves are the anomaly of our party of freedom of religion. That's a Republican way of life, to appreciate freedom of religion, not to impose religion on others.”

Garcia and Amabile both said their lack of religion hasn't been an issue with constituents.

Amabile is on course to become the only openly atheist member of the Colorado Senate, as she has announced a run for an open seat in a heavily Democratic, Boulder-based district. She holds fundraising and name recognition advantages over any potential competitors for the nomination.

"It should be OK to not be religious, and that's part of why I don't want to hide my own lack of belief," Amabile said. "We're supposed to be embracing diversity and allowing for all kinds of identities. ... Religious belief or a lack of one is part of that expression of how we represent people."

Sundaram applauded that approach, noting when all religious and nonreligious populations aren't adequately represented in politics, lawmakers lack valuable perspectives that fluctuate between belief systems and may be unaware of how legislation will influence different faith communities.

“We miss out on seeing the other perspectives that other religious communities would bring and the ways in which they approach issues that might be important to all Coloradans," Sundaram said.

Jodeh and Michaelson Jenet said they've both provided context to legislation based on their backgrounds. Jodeh said she convinced bill sponsors to exempt hookah from legislation seeking to ban flavored tobacco products because of its cultural significance, and Michaelson Jenet said she used Torah teachings to support a bill eliminating the death penalty.

Rep. Richard Holtorf, a Roman Catholic, argued that though the nonreligious community is technically underrepresented in the legislature, their influence is not lacking.

Holtorf, R-Akron, said while the legislature is 61% Christian, lawmakers are not passing Christian legislation. He pointed to recent bills that protect and expand abortion rights as examples.

"Legislation, to be quite honest, is not driven by religion right now with the majority party at all," Holtorf said. "It has nothing to do with it."

Michaelson Jenet raised the same criticism against the minority party.

Michaelson Jenet, who often attends the Capitol's Bible study, said a Christian Republican representative once asked her to read the Book of Matthew. Michaelson Jenet then quoted the book's teachings on feeding the hungry when presenting a bill to make reduced-price lunch free for middle schoolers. The representative voted against her bill, saying he believes in "hand ups not hand outs."

"Where does following your scripture stop? If your scripture says feed the poor, let's feed the poor," Michaelson Jenet said. "I started attending Bible study so that I could relate and learn and hear how they talk about different issues from a faith perspective. But there's definitely a line at the door where those values don't seem to come upstairs."

Sundaram said lack of political representation for any group can also lead to discrimination against communities for being viewed as "un-American," saying it prevents people from seeing "how American values are differently articulated in different religious communities."

Some who spoke to Colorado Politics for this story alluded to that, noting attacks were at times intentionally derogatory to the nonreligious.

Earlier this year, Holtorf called lawmakers supporting abortion legislation "Godless heathens." Rep. Scott Bottoms, a Colorado Springs Republican and Christian pastor, said "listening to God, truth, righteousness and freedom" hurts the souls of lawmakers in favor of gun control.

Lynch articulated similar views to Colorado Politics when recounting how an atheist read a poem during the morning prayer in the session before last.

"I don't remember the content of that prayer, because I was so disgusted that I couldn't focus," Lynch said.

Terrance Carroll, a Baptist minister, served as Colorado’s House speaker in 2009 and 2010. During his time in the role, Carroll said he briefly considered eliminating the morning prayer. Carroll, who also holds a Master of Divinity degree, said he thinks the prayer started off as well-meaning, but “I don’t know if it works anymore” because it is often centered around Christianity specifically.

Carroll said his decision not to get rid of the morning prayer was based on politics, not faith. He feared that it would reflect poorly on Democrats for a Democratic speaker of the House, even one who is a minister, to remove the morning prayer.

"I like to say I'm a Baptist of the old school,” Carroll said. “We believe that every person has freedom of the soul, and that we all have to stand before God on our own one day. That means that I'm free to participate fully in a public square, but I also should not impose my beliefs or dare to speak for God in terms of laws that God would want to have made.”

Lundeen argued that enough concessions have already been made regarding the prayer. In addition to featuring many different faiths, he pointed out that the prayer is now held before the chambers officially convene, allowing lawmakers to be absent: "It's absolutely appropriate."

Future of faithlessness in politics

When Millar joined the Center for Freethought Equality in 2016, the organization knew of five state legislators in the entire country who publicly identified as nonreligious. Today, they're up to 73, plus two members of Congress.

The Colorado legislature's openly nonreligious population has risen from one to six in that same time frame. The total now stands at eight.

Millar said he expects the trend to continue in the coming years.

"The stigma is going away, but it's not completely gone yet," Millar said. "The obvious goal is, at some point, this shouldn't be an issue at all. We shouldn't care what someone's religion or lack thereof is. But for us, for now, it's important because it's one of the most effective ways to get rid of the lingering bias.”

He believes it's yielded a strong track record so far.

Millar said none of the Center for Freethought Equality's candidates have ever lost office after publicly identifying with the group. Though, their candidates are almost entirely Democrats, many of whom hold safe seats.

Server, of the Colorado Catholic Conference, said his organization works with all legislators who promote their values, regardless of the legislator's individual religious identity.

"It is not prerequisite to make good policy to believe and have a religious affiliation," Server said. "There are contributions to the common good from individuals of faith and with faith backgrounds and without faith backgrounds."

Despite this progress, Sundaram said it's hard to know if Colorado's legislature will continue to become less religious in time.

On one hand, younger generations are becoming less religious. This suggests that as members of Generation Z begin to vote and run for office, those offices will become similarly secular.

But Sundaram said Colorado's ethnic makeup might make an even bigger difference. Colorado has sizable and growing Latino and Native American populations, groups that are statistically more religious than the general population. Plus, she said, progressive Christian organizations are working hard to expand their outreach in response to younger generations turning away from religion.

"It's really going to depend on what the electorate looks like," she said.

While the nonreligious are underrepresented in the General Assembly compared to the general population, Colorado is nonetheless leading the nation in nonreligious political representation. Whether the rest of the country is ready to move in that direction or not, Amabile said she's not too concerned.

“Good thing I'm not running for president!" she said with a laugh.